Spiders, snakes, blood, heights, flying — most of us have fearful responses to something in life. This is quite normal. I know very few people who don't have a phobia-type reaction to one thing or another.

In fact, phobias are so common that the DSM (the diagnostic manual used by psychotherapists) only calls something a "phobia" if it interferes significantly with your life, or if you have a great deal of distress about the issue.

In fact, phobias are so common that the DSM (the diagnostic manual used by psychotherapists) only calls something a "phobia" if it interferes significantly with your life, or if you have a great deal of distress about the issue.

As an example, let's say that you're terrified of snakes. However, you live in a large city, and are confident that you'll never see a snake. It doesn't bother you on a day-to-day basis. According to the DSM, you don't technically qualify for a diagnosis of a phobia!

However, that doesn't mean that fears of situations don't affect us in subtle ways. Many of us avoid areas of life based on aversive reactions. I have had clients, for example, who:

The point is that even if a fear doesn't qualify as a diagnosable "phobia,", it might exert a significant amount of influence on your life decisions and plans. Working on managing or reducing the aversion and avoidance associated with phobias can open up many new areas of life.

Before discussing some treatment approaches for phobias, let me be clear about what isn't a phobia.

I am a rock climber, I and occasionally take people climbing outside in Boulder Canyon for their first time. (That's me on Memory of Trees at Watermark, below.)

When I invite friends to come climbing, I often hear them say, "Oh, you wouldn't want to take me climbing — I have a phobia of heights."

I ask them what they mean. They say, "I went to a rock climbing gym once, and when I was half-way up I looked down and got really frightened! I was frozen for a couple of seconds."

I ask them what they mean. They say, "I went to a rock climbing gym once, and when I was half-way up I looked down and got really frightened! I was frozen for a couple of seconds."

I usually say, "That's perfectly normal. When you're hanging in the air by a 10 millimeter rope that's being held by another person, you're supposed to feel some fear! If you were completely unafraid, something would be wrong!"

Fear is sometimes quite appropriate. Although it sounds a bit paradoxical, I am most concerned by the "fearless" new rock climbers that I take out. They usually aren't assessing the risks appropriately, and act recklessly. I actually want them to be a bit more nervous!

So to be clear: the goal of treating phobias and anxiety disorders isn't to get rid of all fear. It's to help the mind learn when it is safe, and also learn when there is a risk that needs attention.

Before talking about the treatment of phobias, let me mention that in the world of psychotherapy there are three common types of phobias:

Specific phobias used to be called "simple phobias," because they are considered less complex than the other two types of phobias listed above. Some of the most common specific phobias include claustrophobia, a fear of being trapped in enclosed spaces; aviophobia (or aerophobia), a fear of flying or airplanes; acrophobia, a fear of heights; and arachnophobia, a fear of spiders.

In cognitive-behavioral therapy, we often use a two-part method of treating phobias:

1. We help our clients to develop new perceptions of and thoughts about the specific triggers; and then...

2. We help our clients to gently and gradually begin to "approach" the triggers while reinforcing the new perceptions/thoughts.

In the first step, we examine "automatic thoughts" that get triggered by the stimulus. These are thoughts that flash very quickly across our minds. For example, someone with claustrophobia might have the following flash-thoughts when he steps foot into an elevator:

In cognitive therapy, we work on identifying these types of automatic thoughts. Then we work on gradually developing new "automatic thoughts" of a more empowering tone. These new thoughts might include:

In cognitive therapy, we work on identifying these types of automatic thoughts. Then we work on gradually developing new "automatic thoughts" of a more empowering tone. These new thoughts might include:

It will take conscious, repeated practice to replace the old automatic thought-pathway with this new thought-pathway. But through practice, the new one will hopefully become stronger and more accessible.

We also work on shifting perceptions of the trigger. Most people with phobias perceive the triggering situations as far more powerful than they perceive themselves. In cognitive therapy, we work to switch this. We help our clients shift their vision so that they see themselves as more powerful than the triggering situation.

Cognitive therapy is based on the observation that a shift in thought/perception leads to a shift in feeling. Our goal is to strengthen these new thought-and-feeling pathways in the mind.

As part of the strengthening process, we begin to gradually and gently "approach" the fearful triggers. We may start with imagination exercises. (This is called "imaginal exposure.") Then we may progress to photos or other images. We gradually work toward approaching the actual frightening triggers, in small steps. The overall process is called graduated exposure.

I want to be very clear about one thing: some psychotherapists (including some cognitive-behavioral therapists) use a "flooding" approach, in which you aggresively confront the triggering situations. For example: these therapists will encourage clients who fear flying to boldly take an airplane flight and directly tackle the fear.

I do not support this! I believe that it risks a full-blown panic attack, and places the client at risk of traumatization. At the very least, it makes the therapy process intensely uncomfortable.

Instead of this flooding approach, I always use a graduated approach. I believe that exposure to triggering stimuli needs to be done gently and gradually, always in conjunction with developing new perceptions and thoughts. Ten small steps are preferable to one big leap.

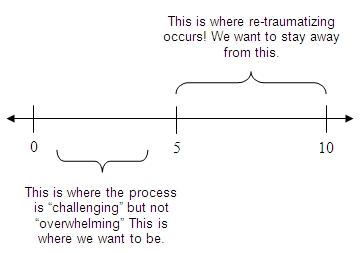

Along these lines, as we gently work on exposure, I encourage my clients to rate their fear-responses on a scale of zero to ten. A five on the scale is where the fear changes from "challenging" to "overwhelming" or painful.

I always encouage my clients to stay below a five. (In fact, we ideally try to stay below a three.)

The goal is to build confidence through "mastery experiences" — experiences that demonstrate to ourselves that we are capable, secure, and able to handle challenging situations. (Including handling the anxiety that arises.)

Again, we do this through a series of small steps. Constructing a way to do this is one of the most interesting challenges in cognitive-behavioral therapy. For example, it's not always easy to figure out how to craft a series of small-step mastery experiences when you're dealing with a phobia of flying!

But through a combination of imaginal exposure, imagery, and then progressive approach steps we will hopefully be able to create a gentle pathway. The goal is to teach the mind that it is safer in the situation than it previously believed.

To return to the anxiety and stress reduction page, please click here.